China-U.S. Trade Law

Try To See It My Way

中文请点击这里

Presidential races in the United States are always characterized by the classic principle connecting domestic to foreign affairs: conjure a foreign foe against whom disparate domestic interests can coalesce. For a very long time, the Cold War provided the Soviet Union. Political campaign disagreement was never about how best to get along. Instead, it was always about which candidate would be tougher on the Soviet Union, which meant asking which one would amass more arms, spend more money on defense, deploy forces to more corners of the globe to combat the Communist threat driven from Moscow. Debates were not about whether to build more missiles, but whether there was a dangerous “missile gap” requiring immediate attention.

The end of the Cold War presented a strategic problem for Americans. Some even imagined it was the “end of history.” Yet, everyone can always find a foreign foe. Even Canada, under Pierre Trudeau, in the early 1980s, thought it could rally domestic unity (meaning committing Québec to Canadian unity) by complaining about the United States. The National Energy Program and the Foreign Investment Review Act were legislative initiatives making the United States Canada’s bogeyman.

During the 1980s, Americans tried out Japan as a potential substitute for the Soviet Union, specifically with regard to Japan’s apparent (and, as it turned out, somewhat illusory) economic rise. Soviet proxies, such as Cuba, remained available, but threatening as instigators, not themselves a danger to Americans. Bitter critics, such as Hugo Chavez, were not taken very seriously. Implacable enemies, such as the Iranian Ayatollahs, were more of a threat to Americans’ friends, such as Israel, than to the United States itself.

September 11, 2001 delivered a new kind of foe and threat, an enemy without a state. Al Qaeda filled a critical gap that President Bush felt impelled to invoke when declaring his war on terrorism as a war with Iraq. But then, the war in Iraq wound down and Osama Bin Laden was eliminated. The United States had gone from the Cold War with the Soviet Union to an economic war with Japan and military conflict with Al Qaeda, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

And then came China, the perfect potential foe against whom all political candidates could agree. The decision-making of the Middle Kingdom was inscrutable, and China obliged the American need for a foe by alternating between pleas for understanding as a developing country and bluster as a rising star and emerging global power.

It has not been enough to conjure China as an economic challenge. Americans have made much of growing Chinese military might, even though China remains decades behind American military capability. Unlike the Soviet Union, there is no talk of missile gaps, but like the Soviet Union, China champions a centrally-controlled economy and a suppression of individual freedoms and free speech. If not a threat to American military security, China is seen by many as somehow a long-term threat to the American way of life.

China bashing has become as commonplace in American presidential campaigns as pledges of fidelity to Israel and hosannahs for the capacities of the American armed forces. It is assumed, within American politics, that post-election the rhetoric and apparent hostility will fade, with the brickbats of campaign promises shaved into chopsticks for shared culinary celebrations.

These assumptions require Chinese to absorb the insults, recognizing them as little more than populist appeals for votes in a democratic society that may exaggerate respect for the ignorant and willfully ill-informed. Yet, now and again diplomacy ought to require a response to the Beatles’ refrain, pleading, “Try to see it my way,” and “We can work it out.” Were Americans to hear comparable criticism from China—if they routinely were called cheaters and pirates, refusing to play by the rules, stealing Chinese jobs, stacking the legal deck—they might not respond with the equanimity and good humor they seem to expect of the Chinese. There may come a point where, as the rhetoric translates into consequential acts, the electoral benefits of escalating attacks on China may be more far-reaching and damaging than the politicians begging for understanding may ever have foreseen.

Giving Substance To Chatter

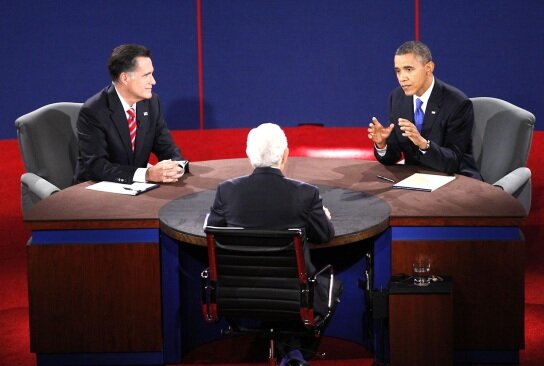

Prior to the presidential debate of October 16, Republican candidate Mitt Romney thundered that, “on Day One” of his presidential term he would declare China a currency manipulator. His action would be insulting, and probably inaccurate (tying one’s currency to the U.S. dollar is hardly manipulative, especially as the ties do not bind and the RMB has floated cautiously upward, as much as eleven percent in the last twenty-four months). And the threat is oblivious to the Brazilian allegation that the United States is a currency manipulator, printing dollars to drive down their value and enhance American exports. Yet, Romney decided to add lightning to the percussion, and whereas the sound might be harmless, the electric bolt of trade sanctions based on the currency manipulation tag could do palpable harm to Chinese trade. During the debate, Romney not only repeated the promise, but added that he would use the new label to impose tariffs unilaterally on Chinese exports to the United States. His amended promise ignored the trade laws, but then the trade laws have not much informed presidential debates.

Just prior to the first presidential debate (October 3), on September 28, President Obama exercised powers granted pursuant to the Defense Production Act of 1950 to order a Chinese wind power industry out of Oregon. It seemed not to matter that he and President Hu Jintao had agreed in 2009 to cooperate in the promotion of wind power.It seemed not to matter that the Chinese enterprise apparently had reached accommodation directly with a neighboring naval facility and had express clearance from the Federal Aviation Administration (which had included Department of Defense review). Instead, the order was swift and abrupt, demanding that the Chinese abandon immediately, without compensation, this investment in the United States. Coinciding with final antidumping and countervailing duty determinations against Chinese solar cells, it seemed that multiple branches of the United States Government were acting in concert against Chinese economic interests.

President Obama persistently has boasted throughout the campaign that he saved 1000 jobs by exercising presidential powers against imports of low-cost tires, largely manufactured by American companies relocated in China. Because the consequence of his action was not to restore the production of these tires in the United States, the claim of saved jobs is doubtful (and no one seems to care where those jobs may be). But imagining them to be real, the Peterson Institute for International Economics has calculated them to have cost consumers, in higher prices caused by the presidentially-imposed tariffs, $1.1 billion, or more than $1 million per job.

There is no debate over any of these developments. Candidate Romney would hardly question an anti-China presidential action, any more than President Obama would denigrate directly the Romney promise on the currency – even though for four years Obama has resisted prudently calls to classify China the way Romney now promises he will, and the U.S. Department of the Treasury has postponed until after the election its statutorily required biannual pronouncement on China’s currency. Instead, there is a soft arms race of anti-China actions and promises. Obama claims to have been tougher on China than any of his predecessors, claims which, in the implementation of Section 421 of the Trade Act of 1974 (the safeguard against tires); the invocation of Section 721 of the Defense Production Act of 1950 (to order abandonment of the Oregon windfarms); and the number of complaints brought to the WTO, are undeniable. Romney, however, promises to be even tougher, particularly as he declares impatience with international organizations and would prefer to act unilaterally.

These economic confrontations are particularly important because both Chinese and Americans identify trade as the single greatest interest they have in common (a majority of the Chinese public, according to the Committee of 100’s recently published Opinion Survey of 2012, and a plurality of Americans). American protectionism threatens Chinese jobs, just as Americans believe unfair Chinese trade practices threaten American jobs. Asked, “What are the two most likely sources of conflict between the U.S. and China in the near future?” a plurality of all American respondent groups (general public, opinion leaders, business leaders, and policymakers) said “trade” first. For every Chinese group, the plurality’s first answer was Taiwan.

Tempering The Rhetoric

By the third and final presidential debate of 2012, on October 22, Romney was retreating from the stridency of his earlier statements. He still insisted upon declaring China a currency manipulator “on Day One,” but he no longer threatened to act further, and his surrogates told the press that the declaration would have little meaning or impact. Perhaps someone had advised him that the President does not have the power to impose trade sanctions unilaterally based upon a presidential declaration of currency manipulation. Or perhaps, as he began believing he might be President on January 20, 2013, he was reflecting on exactly what he was promising.

Romney’s retreat ran deeper. He talked of China as an economic partner, even as he again characterized China as a competitor and adversary.

Obama was not retreating. China continued to test him, not only in trade but in strategic issues. He dispatched his Secretary of State to the Asia Pacific region in September, in the midst of the campaign, reassuring putative allies even as he was not characterizing China as a foe. And he emphasized his WTO complaint over autoparts while reinforcing the actions of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States against the Ralls Corporation’s Oregon windfarm (a subsidiary of China’s Sany Corporation).

Both candidates continued, on and after October 22, to campaign against China almost as much as against each other, but with a new tone and direction. In the October 22 debate, Romney recast his pronouncements on foreign policy to become more an echo of the Obama Administration than a choice. He concurred generally with Obama on the Arab Spring, on Israel and Iran, on North Africa, Afghanistan and Pakistan. And, in the end, on China.

What It May Mean

According to the Committee of 100 survey, Chinese and Americans admire one another, profess to like one another, but do not trust each other. Americans and Chinese see themselves as trading partners, to each other’s advantage, but as competitors with different long-term visions of their place in the world. Chinese generally accept the United States as a lone superpower for many years to come, but also expect one day to surpass the United States.

These views may be more enlightened than those of leaders in both countries. The leaders tend to see the competition as more intense and immediate. They see as much threat as friendship. They perceive a need to speak regularly to what divides China from the United States, perhaps more than what may unite them. The general public in both countries appears more favorable toward one another than their elites, and less ambitious for superiority.

Fortunately for the health and well-being of Chinese-U.S. relations, Chinese leaders are preoccupied with their own imminent leadership change. They respond publicly and vigorously to American slights, of which there have been many, especially during the presidential campaign. But they are likely sensitive to nuance. They will have detected the change in tone in the October 22 debate and the rhetoric thereafter.

By the end of the second presidential debate there was reason to believe that a Romney presidency would cast China as a cold war adversary, changing course from the sophistication of the Obama Administration balancing many Asian and global interests. In the final weeks of the presidential campaign, the Romney strategy has been to seem more experienced by seeming to endorse Obama’s foreign policies. The strategy is designed to reassure Americans that a change in the White House would not mean a radical change in foreign policy.

Romney, despite this strategy, is burdened by advisers who populated the most prominent positions in the Bush Administration. It is difficult to imagine a President appointing advisers with whom he is known to disagree, yet the Romney positions on and after October 22 sound a lot more like Obama, and a lot less like Bush. Should Romney win, the first test will be in whom he appoints, not what he has said. What he was saying before October 22 was consistent generally with the views of his advisers. What he has said since seems closer to what he must believe Americans want to hear. Whether he would govern as he imagines Americans would want, or as his more experienced advisers would tell him, is a question that ought to be of grave concern to China.

If there be a change in course in the Obama view of China during the campaign, it has been to harden positions, but then the 2008 campaign was full of rhetoric about NAFTA that never meant anything for the Obama presidency. China is an almost inevitable target, both because of the international relations principle of identifying a foreign foe, and because China is a soft target in what Americans see as the zero-sum game of jobs. For Obama, protecting the U.S. economy against China – using whatever legal weapons may be in the arsenal – is foremost a campaign necessity designed to reassure Americans that the economy, and employment in particular, are the President’s leading priorities.

Obama must hope that China hears the rhetoric of the campaign – and policy actions during the campaign -- his way, as part of the American electoral process. Romney must hope China sees and hears his way, with shifting positions more the product of campaign necessity than a forecast of untrustworthy or unpredictable conduct. And China must hope that both candidates, at least occasionally, see things the Chinese way, as insulting, presumptuous, but not a threat to a long-term and mutually valuable partnership. All must conclude that “we can work it out,” or leadership in both countries could move the bilateral relationship in unpredictable directions.

美国总统大选的传统特色是将国内政策与外交相结合:树立国外假想敌,并利用这一假想敌把国内利益整合在一起。冷战时期,苏联一直是最好的假想敌。这期间,政治竞选的争议话题不是如何更好和平共处,而是哪位候选人将更严厉地对待苏联——武器竞赛、增加军备开支、增兵海外…….辩论的焦点不是是否应当建造更多导弹,而是导弹配置是否落后、需要立即提升装备。

冷战结束为美国人带来战略难题。一些学者甚至担心这是“历史终结”。但是,每个人都可以随时找到外国假想敌。例如,1980年代初期加拿大总理皮埃尔•特鲁多相信可以通过抱怨美国紧密团结包括奎北克民众在内的全国人民。他推出国家能源计划和外资审查法案妖魔化美国。

同在1980年代,美国试图用利用日本逐渐增长的经济地位取代苏联敌人。苏联爪牙古巴等国依然存在,但是它们并不真正造成威胁。委内瑞拉前总统查维斯的尖锐批评并未引起重视。伊朗等冷酷无情的敌人只对美国友邦造成威胁。

2001年9.11事件制造了新型敌人和威胁——没有国家的敌人。基地组织推动布什总统向伊拉克宣战。现在,伊拉克战争接近尾声,拉登也被消灭。美国从对苏联的冷战进入与日本的经济战,最后卷入与基地组织、伊朗和阿富汗的武装冲突。

中国的崛起使之成为所有候选人共同的潜在敌人。东方大国的决策机制令人费解,中国又在寻求理解的发展中国家和咆哮的、冉冉上升的世界强国两个角色间徘徊,这为美国的敌对论提供了最佳借口。

但是将中国视为经济对手还不足气候。虽然中国的军事实力落后美国十多年,美国却对中国的军事发展忧心忡忡。与苏联不同,美国没有讨论导弹装备差异;和苏联相同,中国也奉行中央控制经济同时限制个人自由和言论自由。即使不把中国视为美国的军事威胁,很多人也把中国视为威胁美国生活方式的长期威胁。

和誓死保卫以色列、祈祷上帝保卫美国军事实力一样,抨击中国的言论成为美国总统大选中的家常便饭。美国政治圈内认为针对中国的敌意论调都将在大选后消退,竞选中许诺的大棒将变成品味美味佳肴的筷子。

这些假设要求中国面对侮辱隐忍不发,将这些言论视为民主社会中为吸引选票而对无知的敬意。但是,外交应响应甲壳虫乐队歌曲《试图用我的方式看世界》(Try to see it my way)和《我们可以解决》(We can work it out)寻求共同点。如果,美国人听到中国不断发出同样的负面批评 ——骗子、海盗、不遵守游戏规则、窃取工作机会,他们会象中国人一样平和、风趣地对待这些指责吗?很可能在不久的将来,攻击中国的言论将带来政客们不曾预料的巨大负面作用。

http://chinaustradelawblog.com/admin/trackback/288775

Washington Square, Suite 1100

1050 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Fax: